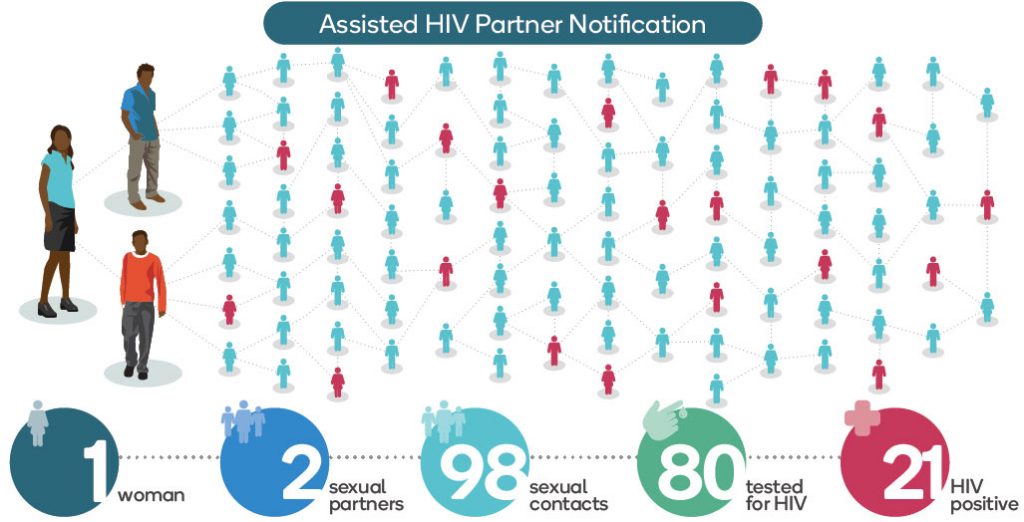

Infographic by Gideon Mureithi and Dustin Marx/Jhpiego.

Ending the HIV epidemic turns on delivering lifesaving drugs that can suppress the virus and reduce the risk of transmission to others. But first you have to identify those who need treatment, many of whom—unaware they have HIV—are transmitting the virus to others. In 2018, 1.7 million people were newly infected with HIV.

This infographic illustrates one case that a Kenyan health provider pursued for more than 6 months in order to reach a network of people potentially exposed to HIV through sexual contact. The provider, an HIV-testing counselor trained in assisted Partner Notification Services (aPNS), was determined to break the chain of HIV transmission and save lives by helping to notify, test and treat the sexual partners of an individual newly diagnosed with HIV, and then those partners’ sexual contacts—and so on. The case began when a young woman who tested positive for HIV voluntarily disclosed two sexual partners. One of those partners, in turn, disclosed seven women with whom he had sexual contact. His contacts led the health worker to their partners, ultimately leading to 98 contacts in the sexual network. Of those, 80 were tested for HIV, and 21 learned they were HIV positive—and offered antiretroviral therapy.

A new approach on partner notification can help save more lives

Kiambu, Kenya—Earlier this year, when a young woman arrived at Lari Level 4 Hospital seeking prenatal care, Peninah Nyambura took the time to explain why it was important to her and her developing baby that she know her HIV status.

Nyambura then offered a test, to which the young woman consented. When the woman’s test results came back HIV-positive, Nyambura counseled her about starting antiretroviral therapy (ART), which involves taking a combination of drugs to treat her HIV and to reduce the risk of transmission to her partners and baby.

Nyambura continued her post-test counseling to discuss notifying her sexual partners through assisted partner notification services (aPNS), a strategy used to break the chain of HIV transmission and save lives by testing and treating the sexual partners of newly diagnosed persons living with HIV and patients on ART. Having recently attended a 5-day specialized training on aPNS, Nyambura had new confidence and skills in this approach and was able to help the young woman understand the urgency of reaching her sexual partners.

The sooner a person learns they are HIV positive, the sooner they can be placed on treatment for their health and the health of others; and if they are HIV-negative, the sooner they can access HIV-prevention services. The young woman agreed to have Nyambura help her, and just how far Nyambura went surprised her.

The search for sexual partners

After the young woman voluntarily disclosed to Nyambura her two sexual partners, Nyambura worked with the woman to contact them in hopes of convincing the men to get tested and treated. One was her former husband, whose whereabouts were unknown. The other, a friend from the neighborhood, was the father of her baby. He showed up for testing the very next day. Upon learning that his status was HIV-positive, he consented to reach out to seven women ranging in age from 27 to 69.

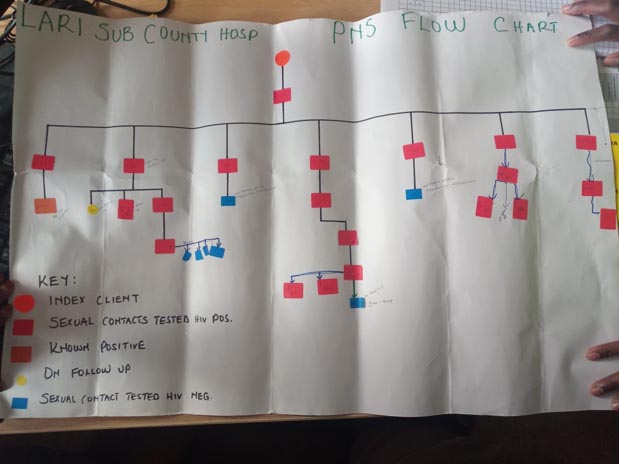

Photo by Catherine Ndungu.

All tested HIV-positive and, in turn, revealed their sexual partners to Nyambura. Nyambura contacted the sexual partners of each person who was HIV-positive, until—over the course of the next 6 months—a total of 98 sexual contacts had been reached. Of those 98, 80 agreed to be tested. The result—21 were newly identified as HIV-positive and linked with life-saving treatment.

In Kenya, where about 1.5 million people are living with HIV, only 1,035,615 (69%) have started ART. A recent study there demonstrated that aPNS can increase identification of partners with undiagnosed infection and uptake of HIV treatment services—with no reports of serious intimate partner violence. It’s a critical strategy toward containing the epidemic in Kenya and globally.

To this day, Nyambura has continued to track down more individuals in need of testing and treatment by identifying the sexual partners of persons living with HIV through the notification services approach. People trust her with incredibly sensitive information. By exercising extreme compassion, ensuring the safety and confidentiality of her clients, and expressing not a shred of judgment, she manages to convince newly diagnosed clients to open up about all of their sexual partners who might be at risk of HIV, not just their primary partner.

While her job might sound straightforward and gratifying, Nyambura also has many examples of calls she makes that don’t get answered, messages she leaves that don’t elicit responses, and partners who aren’t interested in getting tested. Even in Kenya, where HIV testing and treatment have been widely available for many years, stigma and fear are still pervasive, and many people require a lot of time and follow-up before they are ready to get tested. Some clients don’t want to come to health facilities because they are not welcoming or are too far away, so Nyambura also travels to communities to trace partners and offer them testing in their homes. Even then, it is not easy.

“It can be really tough,” Nyambura says. “One time, I had a client release dogs on me!”

An invitation to good health

Funded by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through

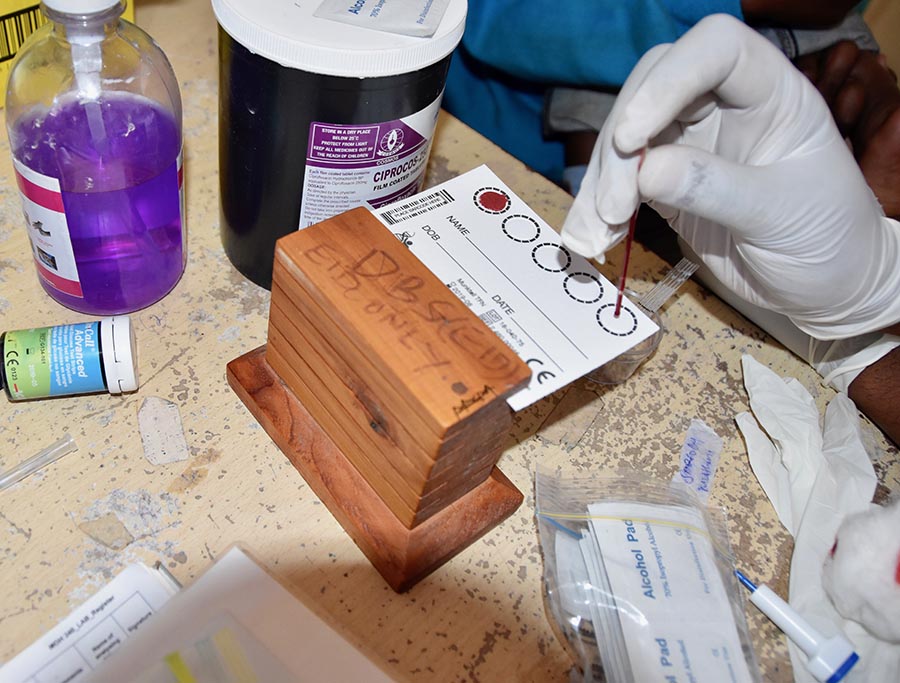

the US Agency for International Development, the Jhpiego-led Afya Kamilisha project recently conducted an aPNS training for new project staff, similar to the one Nyambura attended.

Photo by Catherine Ndungu.

Afya Kamilisha works with health care providers, community health volunteers and others to ensure that HIV-positive clients are linked to treatment and care—even if that means personally escorting them to a health facility or getting them services after traditional working hours. Nyambura is employed by LVCT Health, a local nongovernmental organization member of the Afya Kamilisha consortium for which Jhpiego is the prime partner.

Although Nyambura has spent more than 6 months tracking the sexual partners related to the young pregnant woman, it’s far from the only case occupying her time and energy.

Take the case of a man whose name was revealed to her by a female client who had tested positive. Her initial strategy was to simply invite him to visit a free men’s clinic, at which HIV testing was offered along with a range of services. “It was very hard to get him to come to the clinic,” Nyambura recalls. “I tried over three times before he accepted.”

That he did eventually come to the clinic is a testament to Nyambura’s stellar interpersonal skills, her persistence, and her creativity in addressing the barriers preventing him from accessing these services. When he arrived, he agreed to be screened for blood pressure, diabetes and prostate cancer, among other tests. But when offered an HIV test, he initially refused. Admitting that he was afraid to learn his results, he called his wife for support. She also came to the clinic, and they took the HIV test as a couple. Together, they found out they were HIV-positive and were immediately linked with a health provicer to start HIV treatment.

HIV-positive clients who take treatment regularly are able to live long, healthy lives and reduce the risk of passing HIV to their partners and families. Reducing the risk of HIV transmission is critical to a community’s health, well-being and prosperity. Good health means a parent can focus on the health of the children or work toward a more prosperous future for the family. Healthier families build stronger, self-reliant communities.

Photo by Catherine Ndungu.

“There are no missed opportunities.”

Not one to shy away from challenges, Nyambura has devised strategies to ensure that those most in need of testing and treatment access the services they need.

“The keys to successful partner notification services are maintaining privacy, [confidentiality] and knowing how to navigate the conversation,” she says. “Many clients still have a fear of testing, so it requires [me] to be smart when [talking with] them.

Nyambura has mapped out and connected with health facilities that are outside her assigned area, to ensure that she can help partners who live far away.

“Once a client lets me know their location, I am able to connect them to the nearest health center for . . . testing [and treatment],” she says. “The data are all connected to one system, so it’s easy to follow up, and there are no missed opportunities.”

Catherine Ndungu is a communications manager for Jhpiego in Kenya.

Edith Nyawira is the eMTCT program officer for Jhpiego in Kenya.

Carol Muthamia, an HIV Testing Service Program Officer with partner LVCT, and Maryalice Yakutchik, Jhpiego communications manager, contributed to this story.